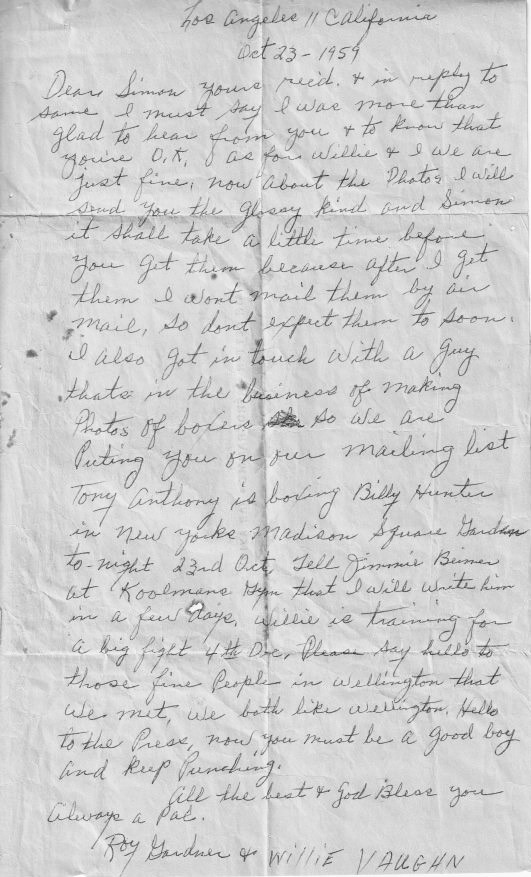

The story of two former boxing opponents — and how one drifted into crime and died violently at an early age while the other became an author.

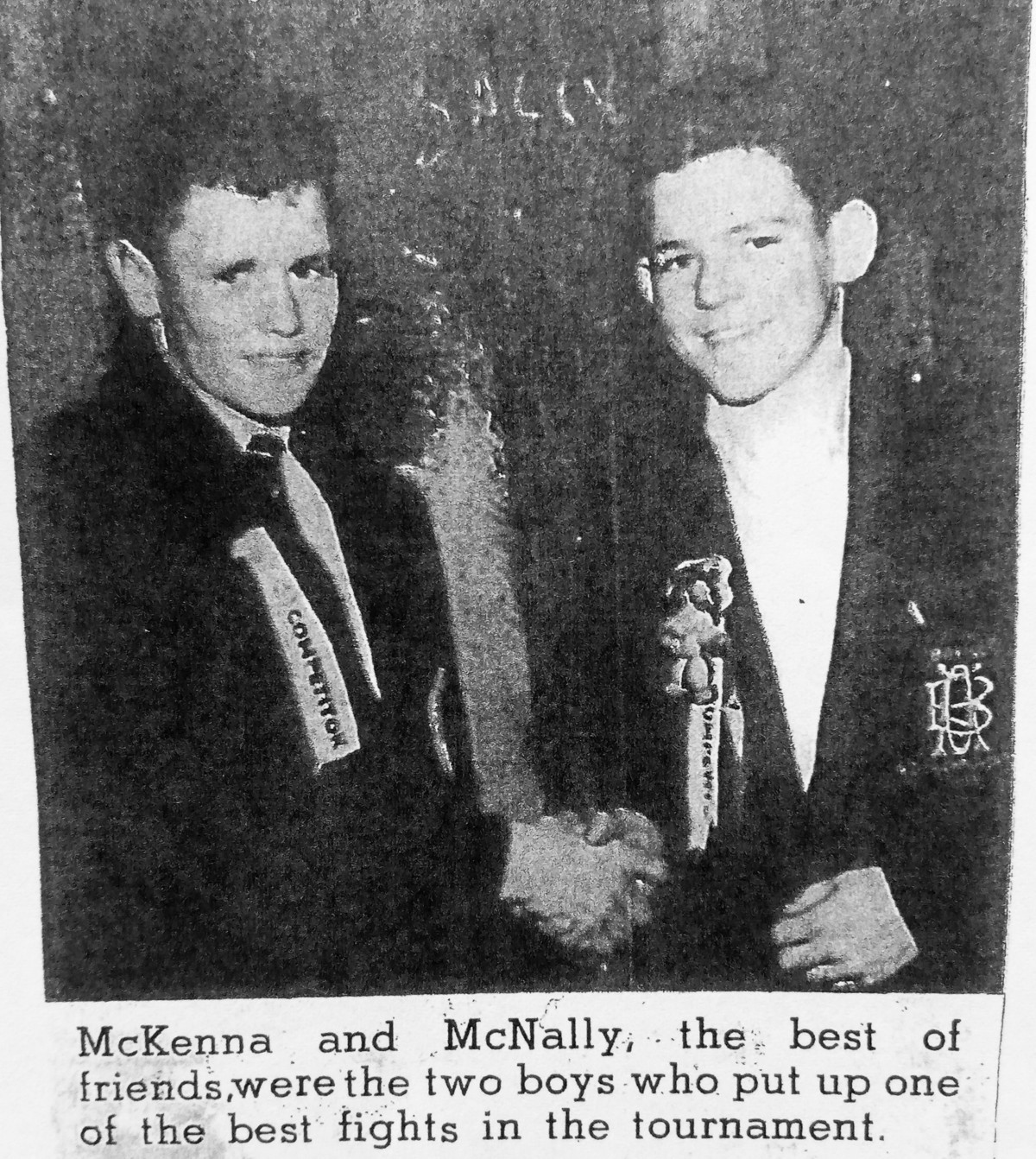

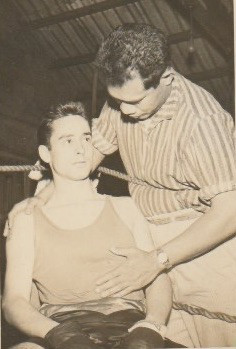

Denis McKenna (left) and Paddy McNally after their 1958 bout in Hastings,

won by McNally on points (Source unknown. Photo supplied by Denis McKenna)

Simon Burnett Takes a Stroll Down Memory Lane

Icy breezes drifting off the southern alps brushed Burnham military camp in the winter of 1963. Inside the wooden barracks was hardly warmer than outside. One recruit, Peter Campbell, recalled his damp face cloth freezing solid overnight.

We struggled to stretch blankets over beds so tight a penny would bounce off them. "Stand by the beds!" Inspection. Snapped orders, yes, sir! No, sir!

Outside, staccato shouts punctured with snaps of military humour Peter told this one:

Sergeant to recruit: Did you shave this morning?

Recruit: Yes, sergeant.

Sergeant: Did you use a mirror?

Recruit: Yes sergeant.

Sergeant: Well, next time use a razor.

Muffled guffaws

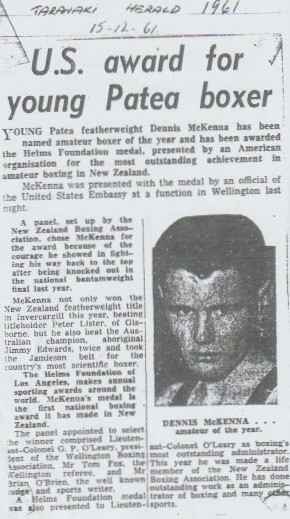

Peter was one of our intake. Another was Denis McKenna, tousle- headed, whipper fit. I knew him by reputation. He had won New Zealand amateur boxing titles in lighter divisions. In 1961 he not only won the featherweight title but also the prized Jameson Belt for the most scientific boxer of the tournament.

I’d seen him box once, in Wellington in May 1962, when he won a close decision on points despite giving away half a stone. The Dominion’s reporter described McKenna as “an Empire Games prospect.” [1]

But this story begins a few years earlier.

A BOY COMES TO TOWN

It is late 1958. A wiry fourteen-year-old strides along Cuba Street, a narrow corridor in the capital city of Wellington. The street is lined by wooden shophouses, slices of classical architecture, the Communist Party HQ, Salvation Army’s no-booze People’s Palace and Clara Hallam’s brothel-hotel known as Lloyd’s.

A global crisis threatens. Soviet premier Nikita Krushchev demands that the western allies — the USA, Britain and France — pull their forces out of the occupied city of Berlin. Cinemas are showing The Young Lions, a World War 2 drama starring Marlon Brando. The world heavyweight boxing champion is Floyd Patterson.

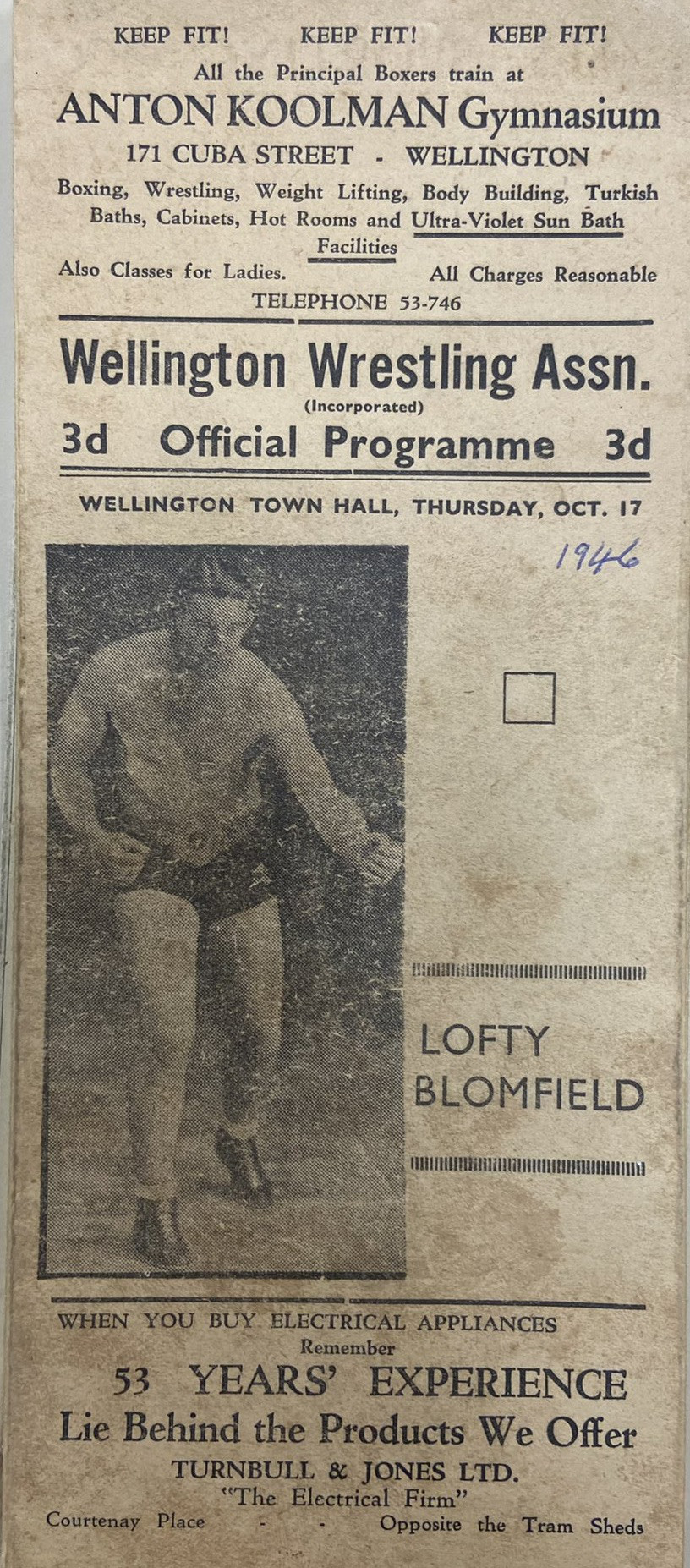

Paddy McNally, boxing prodigy, reaches number 171, enters a gloomy doorway next to a fish ‘n chips shop and climbs the stairs to Koolman’s gymnasium. That’s where I meet him.

As a socially awkward teenager seeking escape from an autocratic father, I hung around Koolman’s. I intended to learn wrestling at Koolman’s, but didn’t have the physique for it. So I was persuaded to take up boxing, for which, I rapidly learned, I had none of the necessary attributes.

I sparred a bit, took part in a few bouts — amazingly winning one, losing three — and revelled in the smells of sweat and liniment and what my adolescent mind perceived as the inspiring company of boxers and wrestlers.The atmosphere boosted my lagging self confidence and low self esteem.

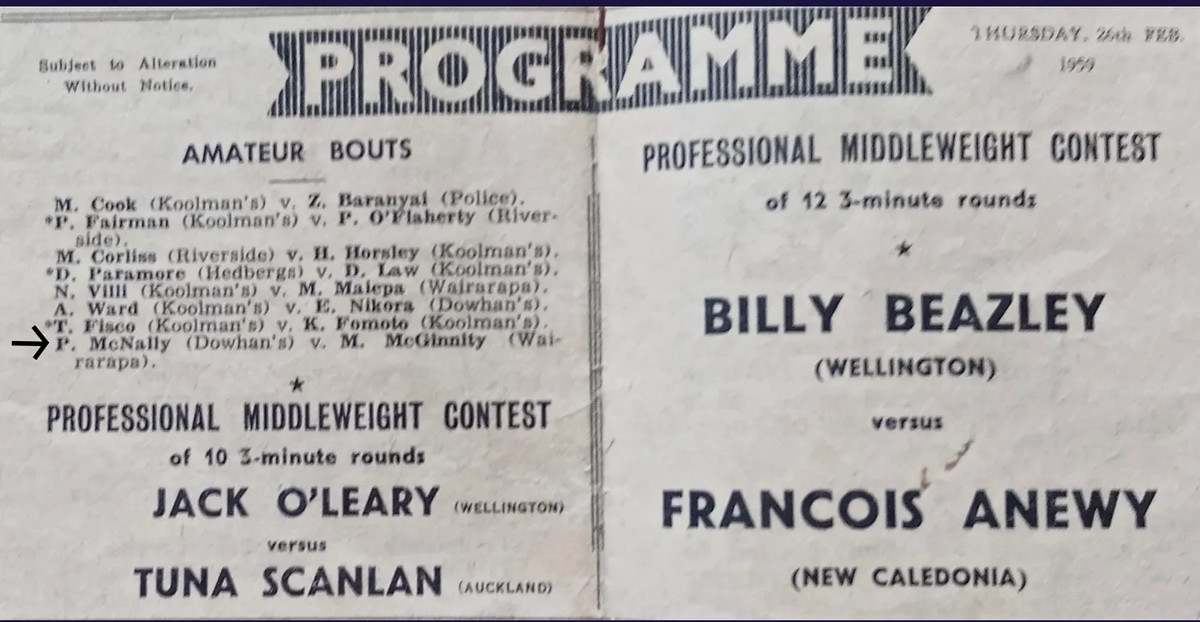

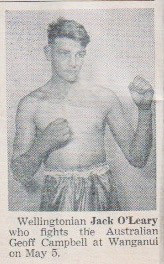

Jack O’Leary trained at Koolman’s. He’d been around for a while, boxing other professional middleweights all over the country. I liked him. Jack — lanky, gaunt, unshaven, friendly — once explained to me how, if he was getting hit too much, he could close up a fight. He demonstrated by dropping his jaw down behind one raised shoulder, holding both gloves high round his face and rolling one way and the other. “I don’t worry what the spectators think. They’re not getting hit,” he said.

Denis on the floor against Paddy,

1959 bout in Wanganui.

(Source unknown. Photo supplied by

Denis McKenna)

The Koolman’s atmosphere was zany. The manager, a heavy-smoking Ulsterman named Jim Beirne, owned a collection of 1920s brassy-schmalzy Al Jolson lyrics (“Don’t cry Tootsie, don’t cry; Toot Toot Tootsie, goodbye”) which blasted incessantly above the thwack-thwack of skipping rope on hard floor.

Paddy, a chirpy kid from the southern city of Dunedin with an impish sense of humour showed not a flicker of uncertainty in his new surroundings. I was still at school. He should have been but wasn’t.

His face lit up in boyish amusement when I showed him the Turkish baths where middle-aged men sat, balding heads protruding from wooden sweat boxes like targets in some comical coconut shy.

He’d already shown himself to be a precocious talent. Earlier in the year, shortly after turning 14, he’d won the New Zealand amateur flyweight title — the senior version — by outpointing another teenager, Denis McKenna, an 18-year old from the Taranaki town of Patea.

In April 1959 — and now based in Wellington — he boxed Denis once more, this time in Wanganui — and won again — by knockout. Yet, it seems, there was more than met the eye to this bout as there was to many things in Paddy’s life.

WILLIE VAUGHN SHOWS HIS PACES

Koolman’s, founded by an Estonian migrant called Anton Koolman who competed as a wrestler at the 1924 Olympic Games, was first stop for visiting boxers and wrestlers. That same April, world-rated American middleweight boxer Willie Vaughn and his affable manager, Roy Gardner, turned up for a bout against the New Zealand champion, Tuna Scanlan.

In those days, a visiting boxer attracted real attention. There was little else. The country was a major exporter of mutton and wool, hardly enough to bring people cheering out of their seats. The British Lions rugby team was due, but that was still a month away.

A familiar figure at Koolman's

..Jack O'Leary (Source unknown.

Image taken from the Wellington

Boxing Association

programme, April 23, 1958)

When Vaughn turned up to train at Koolman’s, Paddy, my friend Paul Moran — an amateur heavyweight boxer and also a friend of Paddy — and I packed into a crowd to watch him spar with local boxers — including Jack O’Leary.

And it was something to see. Our eyes remained rivetted as Jack’s defensive manoeuvres were hopelessly ineffective against Willie’s flying fists. When, after two rounds, Jack climbed out of the ring in front of us, his face reddened, he grinned wryly, and said: “Just as well Scanlan’s fighting him and not me.”

Californians Roy Gardner and Willie Vaughn made a big impact in New Zealand

(The Dominion, April 23, 1959)

None of us had seen anything like this. Paddy turned to Paul and me, smiled tightly and muttered something. We knew what he meant.

The Dominion newspaper reporter commented on Vaughn’s “amazing speed” and said he “has obviously been holding back and, when he started to open up” on the local boys, Gardner told him to “let up." [2]

Vaughn hadn’t had a totally smooth career. He was stopped in eight rounds by Rory Calhoun in June, 1956, after an eleven-month layoff due to manager trouble.

“Vaughn is a fairly clever boxer, a puncher of some ability and a fellow who can take a punch too,” wrote Martin Kane in Sports Illustrated in July, 1956. The loss to Calhoun, continued Kane, “made it clear that long layoffs are bad for boxers like Vaughn, who depend so much on sharpness.”

It seemed now that, with Roy Gardner at his side, his manager troubles were behind him.

On the night of the fight, Paddy and I walked down Cuba Street, past the infamous Lloyds to the grey renaissance-renewal lines of the Town Hall. Even out on the street, we could feel the atmosphere for this, the biggest bout in New Zealand since local boy Barry Brown beat South African Gerald Dreyer for the British Empire welterweight title (as Commonwealth titles were then called) in 1954. We joined the crowd milling in the foyer, said hello to some familiar faces, and headed for the changing rooms.

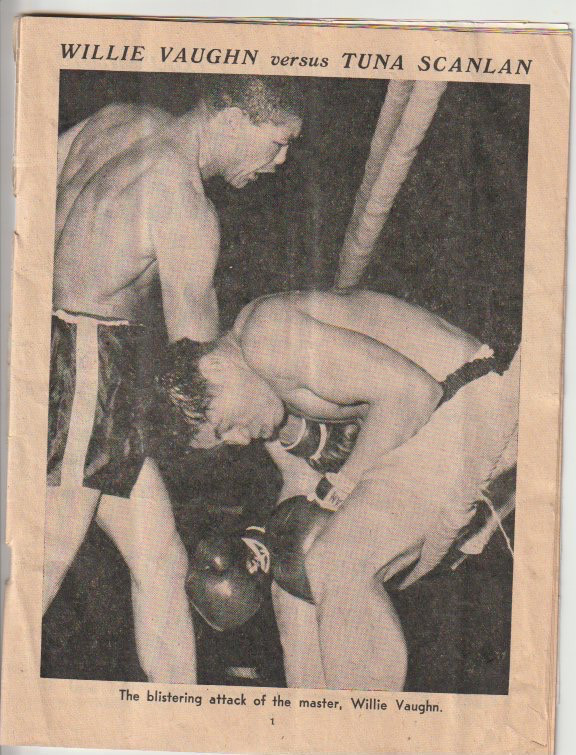

Willie Vaughn (left) knocks out Tuna Scanlan, Wellington. (Source unknown.

Image taken from the Wellington Boxing Association programme, May 18, 1959)

Roy was bandaging Willie’s hands. He looked up, saw me at the door and nodded us in. As a man stood next to them asking questions and taking notes, the usually polite Roy, irritated, muttered, “I’m trying to prepare a fighter for a bout.” Then came an official and ejected the intruder.

Here was Paddy, just fifteen, and me, seventeen, watching the sixth-rated middleweight in the world getting ready for a bout — we were patrician guests in an antechamber of the colosseum, listening to muffled roars filtering through from the amphitheatre.

The tension built. Willie, wrapped in a gown, shadow boxed. The door opened and a blast of noise hit us. It was time to go. Willie rolled his head and shoulders. Roy’s face hardened. Paddy and I followed them out.

Willie, lean and tall, was far too skilled for the short, muscular Tuna, and knocked him out in the fifth round.

A few weeks later, Paddy’s elder brother, Joe, came to Wellington for a bout. A gaggle of media types, ex boxers, hangers on and oddballs drifted into Koolman’s to watch the national professional lightweight champion train. I was expecting someone vaguely similar to Paddy, but there was no obvious resemblance. Joe — eleven years older — was friendly but, by comparison, reserved. [3]

A VISIT TO UNCLE LACHIE

There was another boxing figure in the McNally family — uncle Lachie. One dark Friday evening, with thunder rumbling in the distance, Paddy and I walked up the hill to a quiet back street hidden away behind the railway station. As the first drops of rain fell, we knocked on the door of an unadorned two-story wooden cottage and Lachie McDonald, veteran of 46 professional bouts on both sides of the Tasman Sea in the 1920s, let us in.

(Sydney Morning Herald, April 25, 1928)

He showed us to the living room and settled his bulk in an easy chair. The storm broke. As rain lashed against windows, he reminisced in between fits of coughing and wheezing.

(“Lachie McDonald winner — outfights Monson in torrid 15 rounds — one of best seen at Leichhardt”, reported the Sydney Morning Herald on April 25, 1928)

Paddy was seldom silent. I often had the feeling that a motor buzzed inside him, as if a thousand thoughts were racing through his mind. But tonight, we sat and listened. I had never seen him so still.

By the time we departed the storm had abated. The air smelled fresh. We were elated. We walked back down to the station, neither of us saying much. It was as if Paddy had glimpsed his future stretching out like the lighted city ahead of us.

His life seemed as unencumbered as a scudding cloud. He took jobs but didn’t hold them for long. One morning as I sat in an into-town bus trapped in the usual tailback along the Hutt Road, I saw him, beanie pulled down at a clownish angle, pulling open the double doors of a motor workshop.

When I later mentioned this he grinned in his waggish manner and replied, “Nah. Packed that in.”

But a threatening darkness swelled on the horizon. He asked Paul and me to go with him to visit a friend incarcerated in Mount Crawford prison, high up on the Miramar peninsula east of the city. Paul and I both felt a tingle of pleasure at the prospect of trespassing on, what for us was terra incognita. Sure, we said. But I reached the agreed meeting place late. He and Paul had gone.

Award for Denis (Taranaki Herald,

December 15, 1961)

GLOWING PRAISE FOR DENIS

Here is a curiosity: In 1961, an Australian amateur team toured and boxed a New Zealand team. Paddy fought and easily beat his opponent (I cannot remember who this was, and was unable to find out) and impressed with the speed and cleanness of his punching. Denis was not chosen in the NZ team but the Australian manager, a Mr C. Baxter, said that, of all the boxers he had seen in New Zealand, he was the most impressive. [4]

Denis maintains that his points loss to the 14-year-old Paddy in 1958 was a terrible decision. According to press reports, McNally tired towards the end of the third and last round when McKenna dominated. But less than a year later, they boxed again in the northern town of Wanganui and Denis was floored in the second round. The referee stopped the fight and awarded it to Paddy.

Hell, recalled Denis, Paddy punched hard. But, back in the dressing room when they shook hands, Denis felt his fingers brush something sticky. Paddy unashamedly admitted that he had hardened his fists by binding them with insulation tape instead of the usual gauze. What else he might have used on the tape is not known.

“He was a rogue, “ says Denis, “but a likeable guy.”

PADDY TURNS PROFESSIONAL

In 1962, Paddy turned to professional boxing. I never saw him again. I headed for the South Island where, in Christchurch, I continued my Walter Mitty boxing career by linking up with Lole Fidow, an amiable professional boxer from Samoa who ran his own gymnasium — and where, wisely, I restricted myself to training only — no contests — under Lole’s watchful eye. He was nice enough to keep his opinion of my boxing ability to himself. Then I joined the army.

Someone told me this: Paddy got into a brawl in a Singapore port bar. In the narrow confines, the opponent, an unarmed combat specialist, threw him to the floor. Paddy rose to his feet, reached out a hand in a gesture of reconciliation. When the other responded by offering his own hand, Paddy seized his chance, threw a punch and knocked him cold.

The story might have been fiction, but it did seem to fit his pattern of behaviour, as I would discover.

DENIS IS SENT TO MALAYSIA

Trouble between Indonesia and Malaysia was brewing. Indonesia was infiltrating guerrilla bands into Malaya, Borneo and Sarawak in protest against the formation of the new state of Malaysia. New Zealand was committed to helping Malaysia. Denis and I were both sent to Malaysia, where we were stationed at Terendak Camp, outside the old Portuguese trading town of Malacca.

MYSTERY SURROUNDS PADDY

Paddy grew to welterweight and, perhaps reflecting on the glories of uncle Lachie and Willie Vaughn, headed for the more demanding — and lucrative — arenas of Australia, where he graduated to 12-round bouts.

In April 20, 1964, he beat Alan Roberts at Sydney Stadium. Boxing writer Ray Mitchell noted in Ring Magazine, “Roberts quit in his corner at the end of the seventh round, one eye completely filled.” [5]

But that same year, after 13 bouts and winning eight of them, Paddy stopped boxing. This was strange. He had begun pro boxing with a flurry of eight bouts for six wins in four months in New Zealand. Then came a gap of 18 months with no activity. This was followed by another burst of five bouts (two wins) in Australia in just over two months. Then he quit.

Why the eighteen-month gap? Was he injured? Was he in trouble with the law? Why, just a month after turning 20, would he stop boxing with his best years still in front of him? Was it the training, which he didn’t seem to like but which, had he been more assiduous, might have brought him more wins? The likely answer is that he had found an easier way to make money — but one that would lead him down a perilous path.

PADDY BEHIND BARS

By 1965, as we were trudging through Malaysian jungles, Paddy McNally was doing time in Auckland’s Mt Eden prison where, in a six-metre by six-metre exercise yard, he gave street fighting lessons to other prisoners.

Another inmate, Jim Shepherd (later described as “Diamond Jim” because of his flamboyant tastes), recalls: “Besides boxing skills Paddy showed us a wide variety of his street-fighting talents. We were shown how to use our knees, elbows and head when street fighting. How to punch to the throat, kick or punch directly at an opponent’s testicles as well as the old ‘walnut grip’, grabbing someone’s testicles.” [6]

Shepherd echoed Denis’s opinion of Paddy, saying he “had such an infectious personality he would be smiling at you as he robbed you playing a game of cards.”

Shepherd and McNally would meet up again in Sydney.

DENIS GETS A LETTER FROM GERMANY

The author (left) in 1963 with

trainer Lole Fidow

in Lole's

Christchurch gym. Neither Lole

nor, later, Denis were able to

turn me from chump to champ.

(Photo: author)

By 1966, Denis and I were back in New Zealand. Our discharges were looming. Everyone was optimistically talking about their future in civilian life. Denis decided I should resume my less-than-stellar boxing career. We agreed I would fight under the nom de ring of “Sid Burns” and Denis would be my trainer. [7]

Here, our versions differ. Denis now maintains that, under his tutelage, Sid Burns won a scrap in Ashburton. While Sid does recall being in a boxing ring — and being warned by the referee, Alan Scaife, for a lack of activity — he can’t recall the result, which was likely a points decision against him.

At this time, the war in Vietnam was heating up. I was developing heretical ideas. Some of the battalion had volunteered to go to Vietnam with the New Zealand gun battery but I thought it was a war that shouldn’t even be fought. A year earlier, I had looked down pensively at a Singapore panorama from an upper-floor window, and remarked to a companion, “This will go commo in the next few years.”

But now I no longer entirely believed the prevailing “domino theory” which had it that one country after another in South-East Asia would fall to communism if it were not stopped in Vietnam. I didn’t believe the north’s Ho Chi Minh was such a bad guy.

Denis and I sat in a Christchurch pub with others fresh out of the army, and I cut loose on this theme. They all thought I was merely stirring. “Let’s find a phone,” Denis mocked, “and call Ho Chi Minh and see if he’s at home.”

I left for Australia. Denis went to work in the fast-growing timber town of Tokoroa selling insurance, a flourishing market at that time. He could hardly know that his reputation had spread to unexpected places.

In 1968, he received a letter from Frankfurt, Germany, addressed to “Sir and Gentleman: D. MCKENNA Flyweight Boxing Champion of NZ 1959.” It was from a former boxing manager, Gerd Riethenauer, who, in florid typewritten English (“May I convey today my very sincere compliments and congratulations on you and your excellent and fine and wonderful ring career as the nation’s former outstanding boxer hero. . .”) requested a signed photograph for his boxing archives. Denis complied.

He continued boxing. Then, with a young family to support, he wondered how much he would be paid if he fought as a professional. He was told he could earn 2,000 dollars for each of a string of three fights.

Back then, that was dough. So in 1972, he turned professional. But by now he was in his early 30s, middle-aged in boxing terms. For his first bout, he was matched against a younger opponent, Ron Logo.

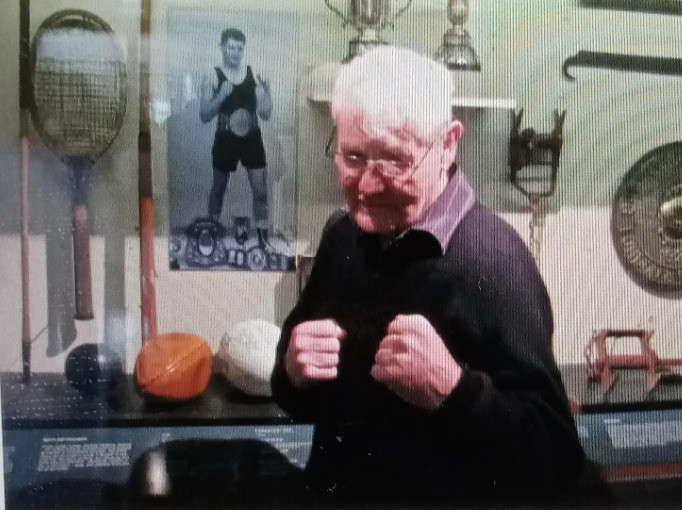

Denis visits museum in 2013 (by kind permission of the South Taranaki District Museum Trust).

“It didn’t work out,” Denis said of his decision to turn pro. He was stopped in the second round. It was a double blow: “It was the only fight of mine that my wife watched.”

He did not box again.

PADDY´S TROUBLES WORSEN

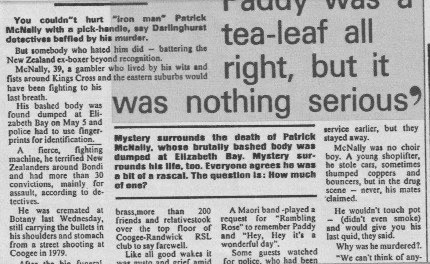

Paddy was in trouble on both sides of the Tasman Sea. In 1975, he was wanted on suspicion of stealing diamonds from a Napier jewellers shop. In Sydney, he was said to be terrorising people in Bondi Beach — popular territory for expat Kiwis — and had picked up more than 30 convictions for assault and stealing from shops.

In 1979, he was accused of stealing a replica of the Melbourne Cup, and, although acquitted, came under police surveillance on suspicion of having gangland connections and distributing heroin.

That year, someone shot him three times after he got into a fight with a hotel bouncer at Coogee. As he lay in hospital, police tried to question him:

“Could you give me a description, please,” the detective asked.

“Yes, I can,” Paddy replied. “He was a large man with a long white beard and he was wearing a red suit.”

“Did he say anything?” the detective asked.

“Yes, he did,” Paddy replied.

“And what did he say?” the detective inquired.

Keeping a straight face, Paddy replied: “Ho, ho, ho.” [8]

This sounds improbable, but it does gain credence from a media report that Paddy refused to give evidence against the man, saying, “it had been a good fight and it wasn’t the other man’s fault that someone handed him a gun.” [9]

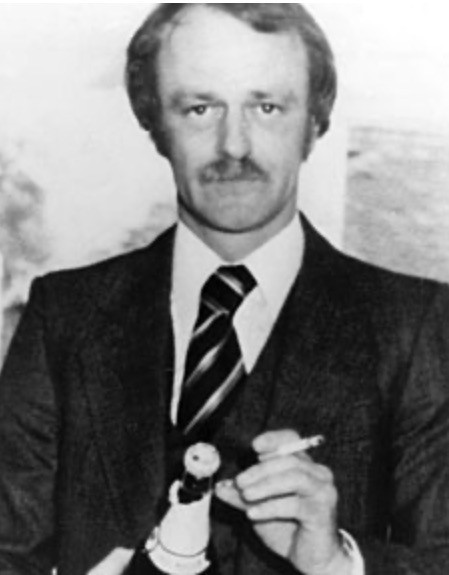

Head of the Mr Asia drugs syndicate Terry Clark (Source unknown)

Ominously, he brushed shoulders with a heroin smuggling gang known as the Mr Asia Syndicate, headed by Terry Clark, a convicted killer (described years later by Shepherd as “NZ’s worst serial killer”. [10]) Paddy was in touch with the gang’s notorious “enforcer”, Peter Fulcher, a New Zealander described by one police officer as “a man almost totally devoid of conscience.”

Fulcher was wanted by Sydney police, but had gone to ground. On September 3,1980, investigators tailed McNally to a house in the suburb of Caringbah where a certain Peter Murdoch was living. [11]

A check with police in New Zealand revealed that “Peter Murdoch” was, in reality, Peter Fulcher.

Fulcher was later arrested and charged with heroin dealing. When the case came to court, Sergeant Robert Treharne of Sydney police told of a meeting he witnessed in a hotel:

“At about 7.50 pm on September 29 I saw the accused Fulcher in the bar area. He approached the bar and purchased a drink. He then walked around the bar area for some time before selecting a seat facing the doorway to Grand Parade, Brighton. At 8 pm, Pat McNally came through that door and took a seat opposite the accused Fulcher.” [12]

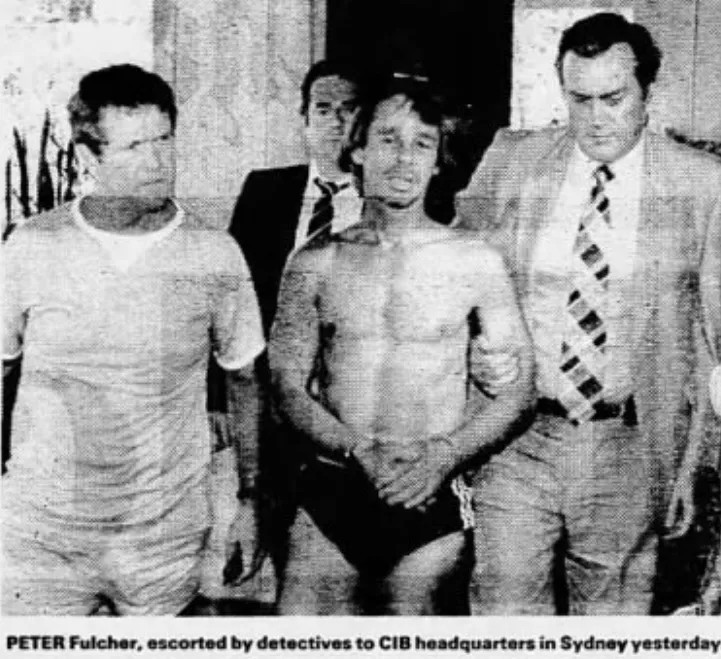

In 1980, police trailed Paddy McNally to find the wanted “enforcer” of the

Mr Asia Syndicate, Peter Fulcher, who was in hiding. Fulcher was arrested, tried and jailed.

Photo shows Fulcher being arrested again in 1985 after having being freed.

(Sydney Morning Herald, January 6, 1985)

Fulcher was found guilty and sentenced to eighteen years’ jail. Paddy was never charged with any drugs offences. He did not return to Napier to face that diamond theft charge.

In February 1983, the Royal Commission into Drug Trafficking named him as a heroin distributor who obtained supplies through James Shepherd, named as the second in charge of the Mr Asia Syndicate — the same James Shepherd he had given fighting lessons to in Mt Eden prison back in 1965. Shepherd had become the banker of the Mr Asia Syndicate, laundering their millions and hiding it overseas.

On May 5, Paddy McNally’s body was found mutilated beyond recognition in the car park of a block of luxury flats in Sydney’s Roslyn Gardens, Elizabeth Bay. He could be identified only through his fingerprints. The killer or killers have never been found. The motive remains unknown.

He was 39.

Paddy named by the Commission into drugs trafficking report, February 1983, page 197

Paddy dies violently (Sydney Morning Herald, May 15, 1983)

1946 advertisement for Koolman's gymnasium in the Wellington Wrestling

Association programme

SISTER CLARE MAKES A PREDICTION

Denis always liked writing. At the Patea convent school the teenager wrote so well that, after reading an essay on gardening, Sister Clare told him, “One day you’ll write a book.” Sister Clare was right.

Denis’s days in the timber town of Tokoroa, sparked an interest in natural resources, an interest that grew over time.

The Sellout of New Zealand, published in 1989 by Resolution Books, dealt with a shadowy global group said to have planned surreptitiously to acquire land and mineral rights both in New Zealand and globally. [13]

There were threats to sue, said Denis, but nothing came of them. He said the book sold 7,000 copies, which is far better than many books today which — including both those of another scribbler, me — merely sell in the hundreds.

He also wrote a follow-up volume, Which Way New Zealand? National Sovereignty or World Government? (“. . . some of our own politicians are involved in this sinister plot to do away with the sovereignty of nations and submerge them into a World Government run through the United Nations.”)

I caught up with Denis on the phone this May — he is not online — the first direct contact we’d had since that meeting in a Christchurch pub in 1966. He lives in Hawera.

Throughout Paddy’s troubled years Denis maintained sporadic phone contact with Joe McNally until the latter was injured in a car crash in 1995. He never left hospital and died in 1998.

The final word from Denis, who still recalls Paddy McNally warmly: “A lot of people say he was just a crook. He was not. He was more than that.”

Cover of Denis's first book